Home > Soapbox > Shrooms with a view

Shrooms with a view

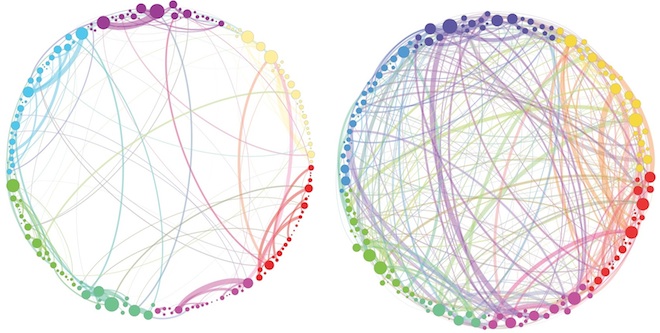

An imaging study shows that people tripping on magic mushrooms have a “hyperconnected” brain, creating temporary networks between regions that don’t typically communicate with each other. Another study showed that the “hot” neural areas for mushroom trippers are associated with emotion and memory, specifically in discrete areas usually most active when we dream, the same areas some people call proto-evolutionary, meaning, the roots of human consciousness.

An imaging study shows that people tripping on magic mushrooms have a “hyperconnected” brain, creating temporary networks between regions that don’t typically communicate with each other. Another study showed that the “hot” neural areas for mushroom trippers are associated with emotion and memory, specifically in discrete areas usually most active when we dream, the same areas some people call proto-evolutionary, meaning, the roots of human consciousness.

Many of us who have experienced trips understand this on some instinctive level, though we may not have articulated it well. And that’s probably how these studies came to be. Eventually, enough trippers, writers, philosophers, dreamers and other people say things about their experiences, a hypothesis is articulated and a study is designed to explore the underpinnings of that which people have experienced. Put data on it. Categorize it. Prove it. Regulate it. That’s the way science progresses.

With human consciousness, however, this process has been halting and labored. In part, it’s because of the challenge to the buttoned-up establishment that psychedelics posed when they first emerged as a tool to manipulate our senses in the 1960s and 1970s. Timothy Leary and his ilk started down a path of inquiry that was cut off hard by the criminalization of this class of drugs.

I’m excited about these recent studies, and the few others like them, that seem to be gaining steam. While directly, these investigations probe the neurological effects of psilocybin — the active psychedelic ingredient in mushrooms — indirectly, they are inquiries into the nature of human consciousness.

The biological basis (or not) of human consciousness may be the greatest scientific question of our era. But it’s tough to study, not only because of the complexity of its interacting parts, but also because the elements of human consciousness are not readily measured and in science, that which cannot be measured does not exist.

But one rudimentary way anything can be measured is by messing with its baseline. The quickest way to understand aspects of how something is ordered is to disrupt its orderliness and then measure whatever randomly pops out in the process that differs from the baseline resting state. Welcome to the toolkit of psychedelics.

Fiction writers — Carlos Castaneda, Aldous Huxley, Ken Kesey and (maybe) Lewis Carroll, to name just a few — have used psychedelics to explore storytelling and, indirectly, the nature of reality as perceived by human consciousness. More recently, a new body of fiction (called con-fi) centered on this topic has emerged, with a focus on near death experiences. In the absence of psychedelics, NDEs are one of the few aberrant baseline comparative access points into human consciousness studies. A study last year showed that death is marked by a surge of brain activity, a hyperconnected state which may be similar to what seems to occur with psychedelic mushroom use.

The location of consciousness provides the context for the concept of The Meta, which rises up in The Cowboy and the Vampire books. Disguised as a genre element in this gothic western series, The Meta provides an opportunity for readers to explore the hypothesis that aspects of human consciousness may be both external and shared. The idea of The Meta came from a variety of experiences, including a brush with death and a youthful indulgence in psychedelics, along with a shared interest in near death experiences and variety of diverse readings — ranging from Richard Bucke to Thomas Nagel. The specific gothic twist manifests as an undead extrapolation of the concept of what many thinkers over the last century have termed cosmic, or collective, consciousness.

I look forward to a day when this concept of shared consciousness gains enough credence to warrant the process of hypothesis development, study design, data collection and so on. A scientific study.

The study need not include vampires.

But setting aside the undead, here’s the scariest question of all and one that fiction writers can (must) tackle: Are our brains even capable of understanding the secrets of our own brains? And what are the implications for our shared human narrative if “no” is the answer?