Home > Soapbox > Cutting to the chase: human consciousness in three books

Cutting to the chase: human consciousness in three books

Increasingly, I’ve noted an uptick of blog posts and references to “cosmic consciousness,” a state-of-being named by Richard Bucke in 1901. I read Bucke’s book Cosmic Consciousness: A Study in the Evolution of the Human Mind more than a decade ago after I stumbled upon it in a footnote of some other equally dusty and neglected book.

Bucke’s cosmic consciousness is a next-gen adaptation, a collective form of shared brain space, which posits eventually we’ll be able to perceive and understand the world through the ties that bind all living things together, be they atomic or energetic or magical. It’s an evolutionary leap in human consciousness, handily explaining the mystical basis of most religions — some humans, like Jesus and Buddha, Blake and, apparently, Bucke, already attained it, and the rest of us, inevitably (if past is prologue) will one day get there too. Just as we shed our scales, pumped out lungs and wobbled up onto land a gazillion years ago, so too will we cast off our embodied singularity and expand our horizons into the planes of cosmic consciousness.

Bucke’s cosmic consciousness is a next-gen adaptation, a collective form of shared brain space, which posits eventually we’ll be able to perceive and understand the world through the ties that bind all living things together, be they atomic or energetic or magical. It’s an evolutionary leap in human consciousness, handily explaining the mystical basis of most religions — some humans, like Jesus and Buddha, Blake and, apparently, Bucke, already attained it, and the rest of us, inevitably (if past is prologue) will one day get there too. Just as we shed our scales, pumped out lungs and wobbled up onto land a gazillion years ago, so too will we cast off our embodied singularity and expand our horizons into the planes of cosmic consciousness.

But why this uptick of Bucke’s book now? My suspicion is that cosmic consciousness may be ready for its 15 minutes of Warholian fame. It’s a model for the mind that fits nicely with the current internet era of “big data” and cloud storage, as writer Ben Sharp aptly captured in the title of his post The iCloud of Human Consciousness. We share everything now, why not our brains?

Humans model our brains in ways that mimic the current thinking of the day, be it religious or scientific, or a battle between both. Indeed, the various permutations of the dialectal debate between the materialist mind model (neuron-snapping machines responding obediently to biologic directives) and the opposite- of-that model (a Cartesian non-corporeal identity, our soul, responding to, well, God maybe) have been at the heart of the human narrative (along with a lot of associated and tragically violent strife) for centuries.

But back to the point.

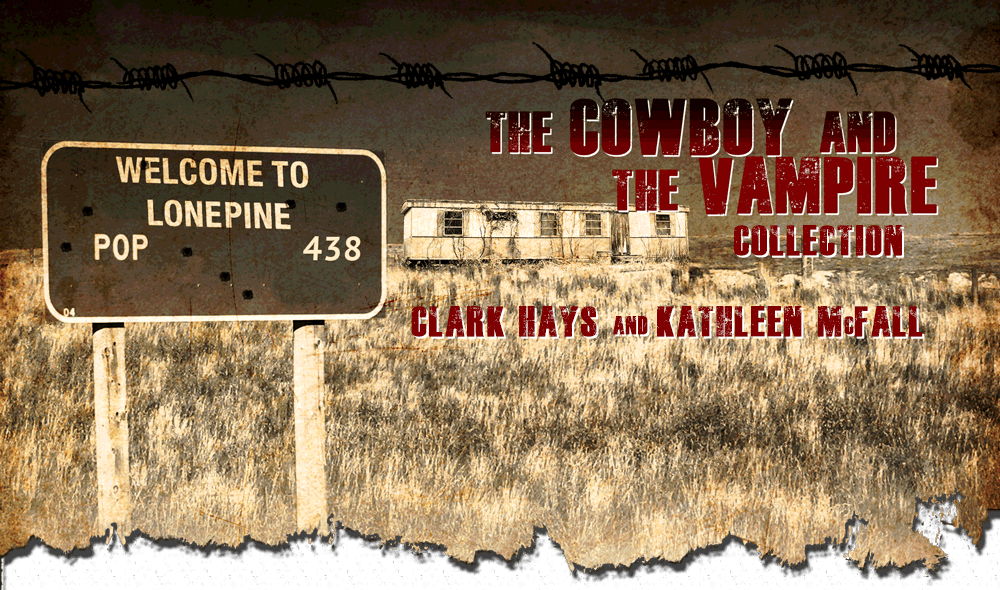

Bucke’s book was foundational to the development of a third way, a dialectical bridge to the theory of human consciousness described in The Cowboy and the Vampire Collection, starting in Book 2. Why cowboys and vampires? We’re not scientists or philosophers, so we explore ideas inside the reputational safety of genre fiction, poetry and graphic novels. We are, of course, not alone in this pursuit.

But it wasn’t just Bucke. Other thinkers influenced our cowboy and vampire theory too (along with a near-death experience). After piles of reading, we’ve winnowed. Bucke’s book emerges as a winner, but the non-Goodwill pile also includes two books which, after being baked in our collective overheated brains, collided into the creation of The Meta, that middle way between rigid scientific materialism and spiritually based temporary embodiment but has, until now, been unnamed. We went ahead and named it: The Meta

Here are the two other books:

Julian Jaynes , 1976, The Origins of Human Consciousness and the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. You know those voices you hear sometimes in the dark and you think its god, or your mom, or maybe spirits from the past? Guess what, it’s just one side of your brain chatting with the other side. At least, that’s how it used to be in some distant pre-now time, before our brains evolved to their cool, current state of integrated-consciousness. Jaynes presents a compelling hypothesis that long ago our split brains (hmm, who doesn’t wonder why we have two halves of a brain) had a hard-stop between them and one side was the dreamy, imaginative side and the other the logical hunting-and-gathering side. The one side dreamed up God and such, the other took its directions. Eventually, they got together, and wham, we leapt up the evolutionary scale to self-awareness.

, 1976, The Origins of Human Consciousness and the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. You know those voices you hear sometimes in the dark and you think its god, or your mom, or maybe spirits from the past? Guess what, it’s just one side of your brain chatting with the other side. At least, that’s how it used to be in some distant pre-now time, before our brains evolved to their cool, current state of integrated-consciousness. Jaynes presents a compelling hypothesis that long ago our split brains (hmm, who doesn’t wonder why we have two halves of a brain) had a hard-stop between them and one side was the dreamy, imaginative side and the other the logical hunting-and-gathering side. The one side dreamed up God and such, the other took its directions. Eventually, they got together, and wham, we leapt up the evolutionary scale to self-awareness.

Thomas Nagel, 2012, Mind and Cosmos: Why the Materialist neo-Darwinian Conception of Nature is Almost Certainly False. Tough book to  read, but there’s enough written around and about it that one can manage to penetrate the jargon to get to the main — and supremely important — message. Here it is: The acknowledge-only-what-you-can-measure premise of science can’t handle the emerging truth of human consciousness. What is the stuff of consciousness? That’s still unclear, says Nagel, but whatever it is, the constraints of the contemporary scientific method and the model of evolutionary biology will never get us to an answer. Read this book (or read what others write about it, it’s pretty dense) and broaden your own mind-stuff. Prediction? This will be considered a seminal book in 20 years, despite the derision it’s received across the scientific establishment.

read, but there’s enough written around and about it that one can manage to penetrate the jargon to get to the main — and supremely important — message. Here it is: The acknowledge-only-what-you-can-measure premise of science can’t handle the emerging truth of human consciousness. What is the stuff of consciousness? That’s still unclear, says Nagel, but whatever it is, the constraints of the contemporary scientific method and the model of evolutionary biology will never get us to an answer. Read this book (or read what others write about it, it’s pretty dense) and broaden your own mind-stuff. Prediction? This will be considered a seminal book in 20 years, despite the derision it’s received across the scientific establishment.

I’ll close with this unrelated but fascinating fact I learned wandering around the biomedical research building at the university recently. All neurological disorders are accompanied by changes in one’s ability to smell. Think about that and see how well you can smell garlic, maybe test that on a weekly basis.